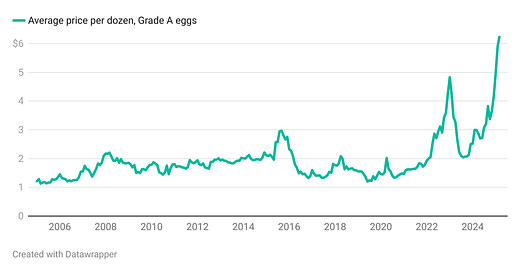

What's that got to do with the price of eggs?

Still very pricey. Time to plan your Easter potato hunt.

Looks like American breakfast isn’t saved after all. Sorry everybody!

I reported on declining egg prices for FT Alphaville this month. This was a fun story, because a big jump in US imports from Turkey and Mexico helped drive at least some of the decline. It also landed right as the White House (briefly) decided to slap super-high tariffs on a bunch of stuff, including food products that can’t really be grown here.

Egg prices did fall, so the story wasn’t wrong. But it only happened for wholesale buyers, which means food companies, bakeries, restaurants, and presumably grocery stores.

The price of fresh eggs at the grocery store — what regular people pay — still hasn’t dropped, according to the latest CPI report. It actually increased in March. Whoops!

So why hasn’t the decline in wholesale egg prices shown up at the grocery store?

It was definitely a big one! The USDA data shows a 63% drop, before prices started to creep higher again ahead of the Easter holiday:

And the jump in imports was also pretty big, going by our most recent data (from February):

And yes, the total amount imported was low compared to the total amount of eggs that Americans eat.

But eggs are a commodity — you can basically substitute any egg for any other egg, notwithstanding what homesteaders say about the superiority of fresh eggs from a home flock. (I might learn about that soon, so uhhhhhh wish me luck, lol, yikes.)

For commodities, an unexpected change in supply, even at the margin, can move prices noticeably. The decline in egg prices was also probably fueled by a decline in wholesale demand. It seems reasonable to think fewer people are buying eggs at Waffle House because of its 50c-per-egg surcharge. If they’re buying eggs to make at home instead, that could boost retail demand for eggs.

Beyond that, though, how do we explain the difference in egg prices between consumer and wholesale buyers?

Let’s suspend our cynicism — at least for a moment — and try to come up with a reasonable explanation besides price gouging I mean, uh, greedflation, er, nevermind, monopoly power, wait OK, let’s call it pricing dynamics that arise from inelastic demand.

Maybe this is simply a consequence of how consumer inflation is measured? Maybe the BLS’s survey logged the price of a dozen eggs on March 1, when prices were still high, and called it a day?

Nope!

When it measures data, the BLS seeks to capture the entire month, and not just one time period during that month (unlike, ahem, some other statistical agencies around the world).

To do that, it splits the month into three periods: Days 1-10; days 11-20; and days 21-30. It measures prices during each of these three periods, and all of them get equal weighting in the final inflation figures.

The BLS gathers the same amount of data in each period, and then smushes it all together (to use highly sophisticated mathematical language) to get a picture of the month in aggregate.

In other words: If consumer prices had fallen comparably fast in March, the BLS’s data would’ve shown it.

What about pricing lags? How long does it take for this type of price move to show up in consumer markets, anyway?

One comparison — not a perfect one, but one that’s worth looking at — is the relationship between crude oil and gasoline.

Oil and gas are commodities, like eggs. But they require a far more work-intensive process to get gasoline out of oil. (Oil needs to be refined into gasoline, while eggs are simply packaged/repackaged and sold.)

Gas stations are a highly competitive businesses, though, so gasoline prices respond pretty quickly to changes in crude-oil markets, as the US’s Energy Information Administration found in a 2014 study:

Statistical analysis demonstrates about half of the change in crude oil price is passed through to retail prices within two weeks of the price change, all other market factors equal.

This is … interesting. The researchers don't delve into whether gas prices are more responsive to rising prices than falling prices. And the last study we found on this topic was from the Dallas Fed in 2003, which seems a little too dated to cite.

Either way, it’s a bracing analogy. Going by CPI data, at least, none of the decline in wholesale egg prices passed through to retail prices. Remember, the BLS found that egg prices increased for consumers in March! (Over the whole month, in aggregate.)

If we use the two-week rule of thumb from oil/gasoline markets, retailers should’ve had some time to pass through their eggcellent savings. That’s because the slide in wholesale egg prices was frontloaded in the beginning of the month: They fell 48% between the Feb. 28 and March 14, and then another 28% from there.

Egg prices did decline in the BLS’s producer price index for March, too:

Unlike CPI figures, the PPI prices are collected at just one point in time, during the week of the 13th each month. And it showed a 21% monthly decline in egg prices.

So, uh, we really are running out of excuses for egg producers and sellers, other than wringing some extra margins out of a price jump that was, at least in theory, caused by avian flu and a squeeze in supply.

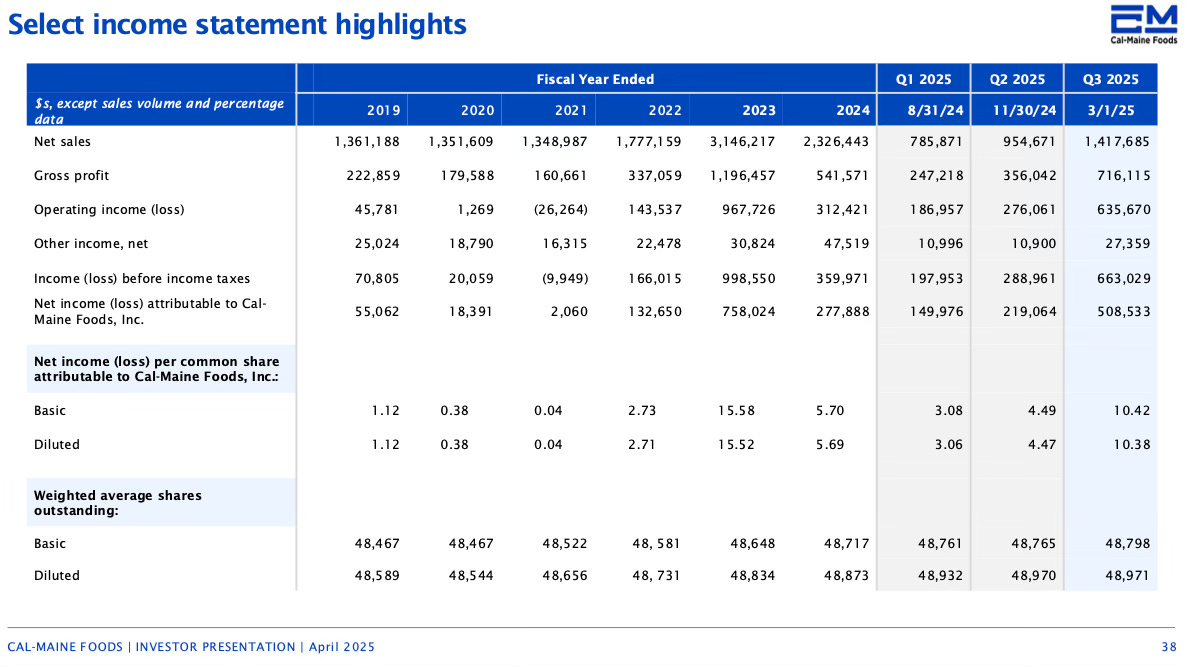

Most of the news stories about egg prices have mentioned Cal-Maine, the only egg producer that’s publicly traded. But their stories mention revenues, which doesn’t really address the central issue here, which is profitability. If Cal-Maine couldn’t provide competitively priced eggs because it was spending big replenishing its flocks after losses from avian flu, its sales would still be fine, but profits would suffer. The company owns 14% of the US’s layer hen flock, according to its latest quarterly report, so it could presumably move the needle (remember, commodities are priced on the margin).

But uh, check out the column on the far right, from its latest investor presentation:

That shows it earned $10.38 per share (diluted) in the quarter ended March 1. That’s 82% more per-share profit than it made for the full year of 2024. It’s already on track to exceed its per-share annual profit from 2023.

It also disclosed a “pending DOJ antitrust investigation” with that earnings report:

In March 2025, the Company received a civil investigative demand from the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) in connection with an antitrust investigation to determine whether there is, has been or may be a violation of the antitrust laws by anticompetitive conduct by and among egg producers. The Company is cooperating with the investigation. Management cannot predict the eventual scope, duration or outcome of this investigation and is unable to estimate the amount or range of potential losses, if any, at this time.

Worth keeping an eye on, at least!

That said, we’ll probably still dye actual eggs for Easter this year. Yes, they’re pricey, but I can’t imagine that it’d be any cheaper to make the speckled white-chocolate-coated peanut butter candy eggs that at least one influencer is marketing as an alternatives.