Markets: They’re in crisis!! Again!!

I’ve covered plenty of financial-market messes, and this one is the weirdest by far. So let’s unpack what’s happened since “Liberation Day”, when the Trump Administration unveiled a baffling round of tariffs that managed to piss off almost every single trading partner. The bad news is the market’s response does probably matter for you.

FYI: I’m going to ignore the stock market, because it doesn’t matter that much here. Stocks have sold off a lot, but they were expensive to begin with. (As of Friday, the S&P 500 was still trading above long-term average valuations.)

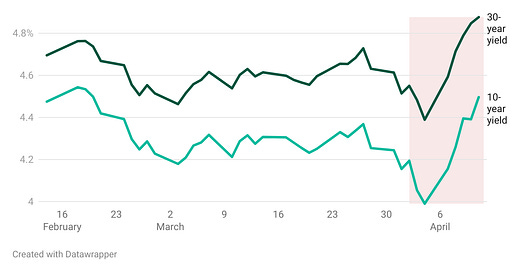

The actual spooky selloff happened in the US Treasury market last week. Prices fell and yields soared.

That isn’t supposed to happen when there’s a lot of investor fear about economic growth, and when riskier markets (like stocks) are selling off.

This is because the US, Europe and Japan are standard-bearers for government creditworthiness. And even within that group, the US has been a standout. This is because it has — or had — three things going for it: 1. the dollar’s preeminence as the currency of global trade (hahaha), 2. very deep financial markets, and 3. a very large domestic investor base of retirement fund managers and insurers.

So when the proverbial blood is in the streets, Treasuries are usually the best place for investors to hide out. This reached comedic extremes in 2011, when the US’s credit rating got downgraded — the rating agencies said it had become less creditworthy — and investors rushed to buy the US’s debt.

Given all of that, it’s really not great that the 10-year Treasury had its biggest selloff since 2001 last week, by Bloomberg’s measure.

If investors were spooked about economic growth, they should’ve bought bonds.

If they were worried about tariffs’ effects on Europe and Japan, they should’ve bought into dollar markets. But they didn’t — the dollar fell against the euro and the yen.

How worrying is this, really?

To answer that question, we need to pick apart whether these market moves were driven by a fundamental change in global investors’ appetite for US markets, or whether we can blame “market technicals” (ie things breaking somewhere, some leveraged trader blowing up, etc).

Sometimes these type of moves in Treasuries really are caused by hedge funds blowing up! In the early days of Covid-19 panic, for example, there were lots of bizarre dislocations between different Treasury prices. That’s why lots of financial journalists spent last week talking about “the basis trade”, which has become a not-especially-accurate shorthand for all leveraged trading in Treasuries.

To be fair, last week probably did feature some type of implosion in a popular derivatives trade, but not the basis trade (an arbitrage between Treasuries and futures markets). Instead, it was a bet on expected bank deregulation. (Look up “swap spreads” if you’re thoroughly financepilled.)

To really cut through the noise, though, the dollar provides a guide.

During the last crisis, the Treasury market went berserk because of hedge-fund unwinds. So what did the dollar do?

That looks very different! During the Covid-19 mess, global investors raced to hoard dollars.

In contrast, after “Liberation Day”, investors sold dollar-denominated investments and bought competing currencies instead. And while China allowed its currency to depreciate during this event, the dollar index we’re using doesn’t include the yuan in its basket of comparisons. So.

This raises some pretty thorny questions about the security of the US’s economic power.

Remember how global trade is a reason the US is especially attractive among reserve currencies? The White House took a chainsaw to that on April 2.

While officials seem to be trying to repair some of the damage — as of Sunday, consumer electronics are exempt? But only for a month? — the sheer disorganization of the rollout makes me wonder if investors might feel a little more comfortable holding their cash in euros or yen, relatively speaking.

One irony here is that US’s debt affordability was one of the issues that DOGE seemed very very concerned with in the early days of President Trump’s second term. The US’s interest costs are pretty high right now, but they’re a weird thing to lose sleep over. No one’s going wild and bidding up the price of goods and services (ie causing inflation) with the income from their bond investments, as far as we can tell.

Here in the real world, the implications of the bond selloff are simpler. Also more important.

Americans buy lots of stuff. So much stuff, in fact, that we can’t make it all here. So other countries produce that stuff, and sell it to us, leaving the world awash in dollars. It’s good for global companies and governments to put those dollars into US Treasuries so they can keep their dollar portfolios liquid and earn a little yield. It’s also good for Americans, because it keeps yields down.

Why are lower yields helpful? Because — lol, lmao — Americans’ debt costs are benchmarked to US interest rates!

Moves in Treasury yields have real and immediate effects on anyone who borrows money, or who works for a company that borrows money, or who buys stuff from a company that borrows money. (Retailers can finance inventory with rotating lines of floating-rate bank credit, for example, though those costs are more closely tied to short-term rates, which are set by the Fed.) That’s all of us, basically.

Want to buy a house? In simplified terms, here’s how a bank sets the interest rate for your mortgage: It’ll take the 10-year Treasury yield, and then add on a spread to pay for the risk that you might default.

The spread is where most of the action happens — credit histories, loan-to-value ratios, etc — but all new mortgages will be more expensive when Treasury yields are high.

See here:

Luckily, Americans get 30-year fixed-rate mortgages to finance our homes, so it’s not a huge deal for people with pre-2022 mortgages. That’s most of them, presumably.

Everybody else is screwed, though :)

Now, I could write all day about borrowing and debt markets, but this is good point to take a look at real, physical commodities.

A mortgage-rate explainer is pointless if there aren’t any affordable houses to buy, and affordability has been a serious problem! So when the financial-market stagflation trade loomed on the horizon last week, the White House’s most vocal supporters started cheering the impending Fire Sale on homes, stocks, and basically everything except for gold. I saw many of these social-media posts at the time, but I can’t bring myself to track them down. It’s been a long week.

But that messaging highlights another question about the White House’s tariff policy and its real-world effects: Are they trying to cause a recession? Do they want to do a speedrun through the Covid-19 downturn so the Trump Administration can claim credit for 3 years of economic recovery?

Kyla Scanlon has already written about this, and the WSJ’s reporting from last week does seem to back it up:

Trump played his cards close to his vest. He told advisers that he was willing to take “pain,” a person who spoke to him on Monday said. He privately acknowledged that his trade policy could trigger a recession but said he wanted to be sure it didn’t cause a depression, according to people familiar with the conversations.

So what does that mean for us?

Homes should get cheaper if there’s a giant recession and a bunch of Boomers are forced to sell their houses to raise cash.

On the other hand… recessions are famously not good for jobs and income, and you need those to buy a house!

You also need lots of stuff to build a house — or to renovate one, because renovations are more important than they used to be. The median US home was 43 years old in 2019, up from 32 years in 2005, according to Goldman Sachs’ calculations. (In 1985 the median home was 23 years old.)

And while everyone was distracted with the changing “reciprocal” tariffs, the US tacked a ~34% tariff on softwood lumber from Canada. Lumber futures were up 25% this year, until we were, uh, liberated from those high prices and expectations of stronger demand. So at least tariffs will be charged on lower-priced wood, I guess:

How are other types of homebuilding and renovation materials affected by tariffs?

Bank of America wrote a note looking at what it would have been, had the Trump Administration actually followed through — ahahahahaafnjkla;djflas I am fine, it’s fine!

The bank wrote on April 8 that manufacturers of carpeting, drywall, insulation, roofing, doors, etc would probably need to increase by an average 1.5%. That isn’t accurate anymore, obviously.

But!!!!

A bunch of price increases have already been announced, thanks to other confusingly implemented and then partially rolled back tariffs. It would be… surprising… to see a company cancel a widely announced price increase, especially when tariff levels change according to the whims of one 78-year-old man. Bank of America summarized a bunch of those earlier price increases in a March 9 note, and they include:

Plumbing manufacturer Masco said prices would go up by 7% for residential customers and 9% for commercial.

LG said it was raising home appliance prices by 6%.

GE appliances — now owned by Chinese company Haier — said it was raising prices by 6-7%. Sub-Zero, Whirlpool and Thermador-Bosch all announced price increases as well.

Flooring manufacturer Shaw Industries announced a 7% price increase on “select products.”

Hey, I wonder how many people get financing for their appliance purchases these days, and what those rates will look like. That’s a topic for a different day, I reckon :)

In summary: Costs of raw housing materials had been going up, more or less, until people started acting like a recession is coming. There’s an indeterminate/confusing amount of tariffs going on materials and appliances, depending on their provenance, sometimes their suppliers’ compliance with trade agreements, and the whims of one man. But prices are probably going up anyway, even with plenty of signs that demand is declining (the BofA analysts observed that too).

So… maybe I shouldn’t follow through with my romantic and completely unrealistic plan to buy and renovate an old Victorian house? Bummer.